Blog Archives

What is Counter-Fantasy?

Counter-Fantasy: noun – a subgenre of science fiction

Counter-Fantasy: noun – a subgenre of science fiction

There are, as I see it, two major subdivisions of speculative fiction.

There’s science fiction, in which the setting and all (or at least most) of the props and trappings have a basis (albeit sometimes implausibly) in known science. Within the context of the story, the aliens, whiz-bang technology, and special effects are presumed to be scientifically explicable. We may not know how to create warp drive or gravity plates, for example, but if the people of a science-fictional universe figured it out, the story implies that they did so using scientific principles and (importantly) without violating any known laws of physics.

And then, there’s fantasy, in which imagination has free rein to disregard physics, or any other scientific constraint if the author so chooses. In fantasy, mythological creatures, mystical forces, and magic dominate the setting, and their scientific inexplicability (or impossibility) is no detriment to their existence within the story.

This is, of course, a purely academic distinction. It defines different genres of fiction, but individual stories are often a mix of several. Fantasy, romance, sci-fi, adventure, comedy, and mystery can all coexist happily in a single and entirely enjoyable story. Star Wars is one well-known example that mixes both science fiction and fantasy. The setting, with its space ships and blasters, looks like science fiction, but it’s the mystical Force that drives the story.* If you want to attach a genre label to it, ‘science fantasy’ works about as well as any.

But, getting back to reality…I mean fantasy, there is a subgenre sometimes referred to as ‘magic realism’. This may sound like an oxymoron, and I suppose in some ways it is, but stories in this subgenre place magic and supernatural elements in a setting that otherwise feels realistic. Within the story, the characters may regard magic as an ordinary part of everyday life. The distinction between natural and supernatural doesn’t exist. While immersed in the story, the reader is encouraged to suspend disbelief and accept that the magic could exist in the real world.

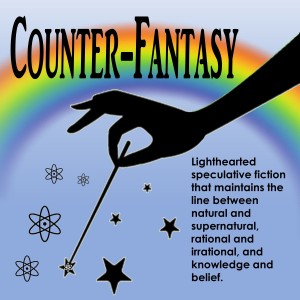

Counter-fantasy is the reverse of that. The stories are set in worlds that feel like traditional fantasy, but either the magic doesn’t work the way characters in the story think it does, or it is clear to the reader that the magic can only exist within the confines of the fictional fantasy universe. Rather than blur the line between fantasy and reality, it emphasizes it.

The idea for counter-fantasy came to me due to the influence of two great writers, Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett. For reasons I could not explain at first, their books seemed different from those by other writers. I enjoyed them more, and it wasn’t simply because of the humor. After several re-readings, the underlying reason finally dawned on me**; they don’t ask me to suspend disbelief for the sake of the story. They don’t require that I abandon reason, intellect, or common sense to visit their fictional worlds. It is always clear that their settings are not real and that the reader is not supposed to believe that they could be real. They’re fiction, pure and simple. The stories aren’t to be taken seriously, but, at the same time, they present serious truths beneath the absurdity. They do what traditional fairy tales were intended to do. They provide a clearly fictional example to convey a serious nonfictional point.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a short book about some poor sap named Arthur Dent who hitches a ride with belligerent aliens just as they’re blowing up Earth…but that part of the story is nonsense. The aliens are ridiculous. Their motive of creating a hyperspace bypass is absurd. It’s a surface story, and the reader isn’t supposed to regard it as anything other than that. It is simply an entertaining framework that ties together several observations about humanity, from the soulless momentum of bureaucracy to the human search for meaning in a vast, uncaring universe. Kind of depressing, that, but couched in humor, the point, the ultimate point in the book comes through. Don’t Panic! The universe is what it is, it will do what it does, and if we think we can make much of a difference in that, well, that’s funny.

Terry Pratchett’s Discworld fantasy stories make a different point—several in fact***. They don’t laugh at the ultimate absurdity of human action; they stress its importance. Humans choose what they will do and what they will be. This may not matter to the overall fate of the universe, but it matters to individual people and to those around them. Pratchett’s stories address greed, sexism, prejudice, jingoism, religion, belief, tradition…. And they do so in stories featuring witches and wizards. But unlike magic realism, Pratchett isn’t trying to make the setting feel real. After all, the stories take place on a flat world resting on the backs of four huge elephants standing atop a planet-size turtle. This absurdity provides a constant reminder that the surface story is fiction and shouldn’t be regarded as anything else.

Both of these great authors create superbly entertaining stories that readers should not take seriously to convey points that they should. That’s what I saw in them, anyway, and that’s what most impressed me. I have a fairly skeptical nature. I don’t suspend disbelief easily, and both Adams and Pratchett provided meaningful and enjoyable stories that didn’t require me to.

A lot of modern fantasy, and even some science fiction, carries a serious tone that clashes with settings that simply cannot be taken seriously. Basic absurdities are presented as if they are not. It’s as if the author expects the reader not to notice clear violations of the laws of gravity, motion, thermodynamics, or probability. Perhaps I have a hair-trigger BS**** reflex, but things like this tend to ruin the story for me. If the story has a serious tone and I read, for example, that some witch or wizard turned someone into a frog, my immediate reaction is, “Where did all the extra mass go?”*****

The thing is, I like fantasy. I enjoy fairy tales. But a good many of the more recent fantasy stories I’ve read (or began to read and gave up on) seemed to take themselves far too seriously. It was as if the writers forgot the meaning of fantasy. It’s not real.******

So, that’s how I got the idea for counter-fantasy. It’s lighthearted speculative fiction with a fantasy-like feel, but it doesn’t try to make the fantasy elements in the story seem as if they could exist outside of it. It maintains, even emphasizes the lines between natural and supernatural, rational and irrational, and knowledge and belief. This, I hope, allows readers to enjoy the story without triggering their BS reflexes. It’s a bit less immersive, a bit less escapist than some fantasy, but I think it provides a good alternative for readers who like to keep one metaphorical foot grounded in reality even when enjoying a work of speculative fiction.

———————–

Footnotes:

* I’m fairly sure George Lucas intended Star Wars to be a fairy tale with space ships. “A Long Time Ago in a Galaxy Far, Far Away…” is far too much like the traditional fairy tale beginning (“A Long Time Ago, In a Land Far Away…”) to be a coincidence.

**I can be a terribly slow learner at times.

***With over 40 Discworld books in the series, a lot of points can be made.

**** BS, of course, stands for Balderdash & Stupidity. What else could it possible mean?

*****In Pratchett’s story A Hat Full of Sky, a young witch turns an unlucky fellow into a small frog and Sir Terry wisely notes that the extra mass manifests as a pink blob nearby.

******Sometimes, I also suspect that there must be some kind of competition going on to see who can create the darkest, most depressing, and unenjoyable books possible, but that’s a separate issue.

————————-

Related Posts:

- 2015 Towel Day / Wear the Lilac Day – https://dlmorrese.wordpress.com/2015/05/24/2015-towel-day-wear-the-lilac-day/

- The Difference Between Science Fiction and Fantasy – https://dlmorrese.wordpress.com/2012/04/21/the-difference-between-science-fiction-and-fantasy/

- More on the Difference Between Science Fiction and Fantasy – https://dlmorrese.wordpress.com/2013/10/15/more-on-the-difference-between-science-fiction-and-fantasy/

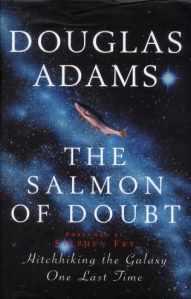

Some Thoughts on The Salmon of Doubt by Douglas Adams

Douglas Adams died in May 2001. He was barely 49 years old. I read all of his published novels up until then, but I never read The Salmon of Doubt until now. It was published the year after his death, and it presents a collection of his writings including chapters from an uncompleted and largely neglected manuscript that he originally intended to be the third Dirk Gently novel, although he had been toying with the idea of rewriting it as another Hitchhiker’s Guide story.

Douglas Adams died in May 2001. He was barely 49 years old. I read all of his published novels up until then, but I never read The Salmon of Doubt until now. It was published the year after his death, and it presents a collection of his writings including chapters from an uncompleted and largely neglected manuscript that he originally intended to be the third Dirk Gently novel, although he had been toying with the idea of rewriting it as another Hitchhiker’s Guide story.

The reason I think I avoided reading it was that the story would never be finished. The world would never see another Douglas Adams novel, and this, I thought, was too sad to think about. So I didn’t. I suppose I was doing the emotional equivalent of throwing a towel over my head, hoping that if I didn’t acknowledge this disturbing thought, it would go away.

I recall a conversation I had with a coworker in 1999. He was a smart young man, well read, but with what I considered a distorted view of the universe. He was a philosophical adherent of the strong anthropic principle, claiming that this provided evidence of a purposeful universe. My own perspective on the issue was more like the one Adams relates in his puddle analogy.

Imagine a puddle waking up one morning and thinking, “This is an interesting world I find myself in — an interesting hole I find myself in — fits me rather neatly, doesn’t it? In fact it fits me staggeringly well, must have been made to have me in it!” This is such a powerful idea that as the sun rises in the sky and the air heats up and as, gradually, the puddle gets smaller and smaller, it’s still frantically hanging on to the notion that everything’s going to be alright, because this world was meant to have him in it, was built to have him in it; so the moment he disappears catches him rather by surprise.

On one occasion, our conversation turned to novels, and I asked him what he thought was the best novel ever written in the English language. He mentioned a few candidates from classic literature. I smiled and shook my head.

“You don’t agree?” he said.

“Nope.”

“What would you say, then?”

“The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” I replied.

He laughed, obviously thinking I was making a joke. He was wrong.

The reason I think The Hitchhiker’s Guide ranks among the best, is that it shakes our complacency about our place in the universe. It takes us, collectively and individually, out of the center, much as Copernicus and Galileo did when they wrote that Earth was, well, not the center of the universe. Adams was more subtle and far more entertaining about it, though, and brought the idea to us not from a scientific or philosophical perspective, but from that of a normal guy, Arthur Dent. He might be the last human in the universe, and, you know what? The universe doesn’t care. It’s not here because of us.

This may seem irrelevant, but it has much to do with Adams and his view of the world, which is really the focus of The Salmon of Doubt. If I were forced to place it in a category, I’d have to call it a biography, although the final twenty-five percent or so is an unfinished novel. The prologue (written before Adams’ death) and the introduction (written after) are certainly biographical. Much of the first section, aptly named “Life,” is autobiographical. The second section, “The Universe,” includes entertaining articles Adams wrote for various publications, selections from interviews, and other bits and pieces. Together, the first two sections provide a good look at this quirky genius. Here are a few highlights:

- Work habits – A procrastinator

- Approach toward writing – He found it slow and difficult

- Attitude toward technology – Fond of gadgets and gizmos and loved his Apple computers

- Religion – Atheist (He didn’t seem to consider this a matter of belief so much as a conclusion that theism wasn’t a rational hypothesis.)

- Favorite alcoholic drink – Whisky (although he was also fond of a properly prepared cup of Earl Grey tea)

- Music – Favorites included the Beatles, Bach, Procol Harum, and Pink Floyd

- Hobbies – Scuba diving

- Interests – Science, Technology, Rhinoceroses

- Favorite kind of food – Japanese

- Favorite authors – P.G. Wodehouse, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Kurt Vonnegut, Ruth Rendell

- The book that changed his life – The Blind Watchmaker by Richard Dawkins (with whom he became good friends)

The last section of the book, “And Everything,” includes two short stories, The Private Life of Genghis Khan, and Young Zaphod Plays it Safe. Both are fun. It also includes eleven chapters compiled from three different versions of his uncompleted novel, The Salmon of Doubt. As presented here, this is a sequel to The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul. I enjoyed it. Dirk Gently is back, and he has a mysterious client, but he has no idea what he’s being paid to do or who is paying him so well to do it. Unfortunately, we never find out, although I have my suspicions. It brings back Kate, who now seems to be cohabiting with Thor, and it answers the question I had about the eagle from Teatime. I’m glad to have that resolved.

I never met Douglas Adams and obviously, I never will. After reading this book, though, I feel I know him a little. I know I owe him a lot, not just for the books I spent many hours reading and laughing through, but also because he was one of the writers who inspired me most to write my own stories. I wish I could thank him for that, or blame him. I would love to able to talk with him and ask him how he made it look so easy when it is really so hard. Mostly I would just like to have him back to let him know I appreciate what he did. I wouldn’t even badger him to write more stories.

Okay, that last bit is probably a lie.

Related Posts:

Book Review – The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul

Book Review – Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency

Book Review – Shada

In Recognition of Towel Day

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

In Recognition of Towel Day

There are other holidays and commemorations, but none is as important, significant, popular, meaningful…

Let’s start again.

Towel Day 2012 will be widely celebrated, observed, recognized…

Fans of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy will recognize this book’s immense contribution, significance, importance…

…

……

……….?

Okay. Towel Day is fairly obscure, if you are judging it based on reality, but, as Douglas Adams reminds us in The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, “reality is frequently inaccurate.” (I’ll get back to that.) The point is that Friday, May 25, 2012 is Towel Day, a commemoration of the life and work of Douglas Adams, and especially of his book The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The first Towel Day was held in 2001, two weeks after Adams’ death on May 11. Fans around the world are encouraged to carry a towel with them on May 25th of each year in his honor.

Why a towel? Well, if you are acquainted with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, you know. If not, here is what it says (in Chapter 3) about towels.

“A towel, it says, is about the most massively useful thing an interstellar hitchhiker can have. Partly it has great practical value. You can wrap it around you for warmth as you bound across the cold moons of Jaglan Beta; you can lie on it on the brilliant marble-sanded beaches of Santraginus V, inhaling the heady sea vapours; you can sleep under it beneath the stars which shine so redly on the desert world of Kakrafoon; use it to sail a miniraft down the slow heavy River Moth; wet it for use in hand-to-hand-combat; wrap it round your head to ward off noxious fumes or avoid the gaze of the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal (such a mind-bogglingly stupid animal, it assumes that if you can’t see it, it can’t see you); you can wave your towel in emergencies as a distress signal, and of course dry yourself off with it if it still seems to be clean enough.

More importantly, a towel has immense psychological value. For some reason, if a strag (strag: non-hitch hiker) discovers that a hitch hiker has his towel with him, he will automatically assume that he is also in possession of a toothbrush, face flannel, soap, tin of biscuits, flask, compass, map, ball of string, gnat spray, wet weather gear, space suit etc., etc. Furthermore, the strag will then happily lend the hitchhiker any of these or a dozen other items that the hitchhiker might accidentally have “lost.” What the strag will think is that any man who can hitch the length and breadth of the galaxy, rough it, slum it, struggle against terrible odds, win through, and still knows where his towel is, is clearly a man to be reckoned with.

Hence a phrase that has passed into hitchhiking slang, as in “Hey, you sass that hoopy Ford Prefect? There’s a frood who really knows where his towel is.” (Sass: know, be aware of, meet, have sex with; hoopy: really together guy; frood: really amazingly together guy.)”

Now you know what the Guide says about towels. You can ignore the rest of this because I’m about to get philosophical and impart symbolic meaning to things Adams may not have intended. Yeah, the symbol is the towel and it relates a bit to the quote about reality being inaccurate. I think he’s right — sort of — in a way. It’s not because there is no objective reality. I’m fairly certain there is, it’s just that I don’t think many people actually live there. People wrap a towel of subjectivity around themselves and interpret reality through it. They see things that are not really there (like I’m seeing the symbolism of the towel) and ignore things that are, sure that if they don’t see them, they can’t cause any harm, rather like the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal. Adams may be pointing out how people filter their perceptions to create personal subjective realities, and I think one of the themes of the book is that we can take these subjective realities far too seriously. Using humor and absurdity, he helps us realize that our beliefs are choices, our perceptions are subjective, and our fears and problems are often simply a matter of how we look at things. Sometimes, our subjective interpretation makes problems of things that don’t need to be, or at least make them seem larger. Shifting perspective may be all that is needed to eliminate a problem, or at least make us feel better about it.

On the other hand, I’m probably taking all of this far too seriously, and one thing I think Adams would caution against is taking anything too seriously, especially his books. So, with that in mind, let me just wish a Happy Towel Day to all you hoopy froods. I hope you remember where your towel is, and, whatever you do, Don’t Panic!

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Let me start out by saying that I found this book mind-bendingly hilarious. There are those who will disagree, some who found it silly, pointless, or even unreadable and all I can think of is that they just didn’t get it. (Just check out some of the reviews on Amazon.) Of course as with music, art, and food, not every book will appeal to everyone. This one appealed to me though and I think it ranks as a notable work of speculative fiction. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy forces readers to see the world from a different perspective and it drags them to this new vantage point laughing all the way if they allow it to, if they can suspend their disbelief long enough to let it. It begins with Arthur Dent doing the mundane things all of us do in our mundane world, shaving, brushing his teeth, and then he suddenly realizes that his house is about to be knocked down to build a bypass. Shift perspective. His normal routine is disrupted by a new, bigger picture. He is trying to stop the bulldozers when his friend Ford Prefect shows up. He has something important to say to him and he wants to say it at the local pub. The Earth is going to be destroyed to make way for a hyperspace bypass. Shift perspective again. His world has gone from being, well, the whole world to a minor nuisance so much so that the only reference to Earth in the Encyclopedia Galactica is that it is “mostly harmless.” And then as the book progresses it continues to challenge some very fundamental assumptions. Is the universe really as orderly and logical as we assume it to be or do the laws of nature we understand amount to just one of an infinite number of possibilities? What really is the meaning of life, the universe, and everything—and does the question really make any sense? But whatever infinitely improbable circumstance you may find yourself in, the Hitchhiker’s Guide provides one bit of sagely advice—DON’T PANIC!